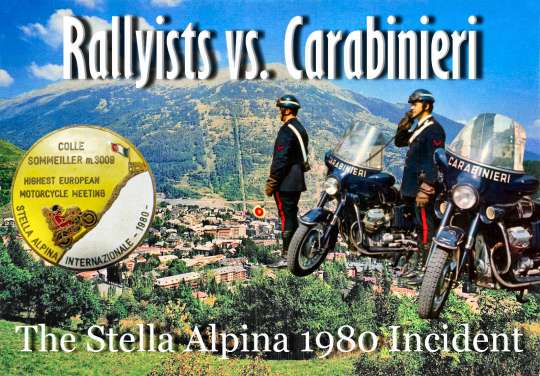

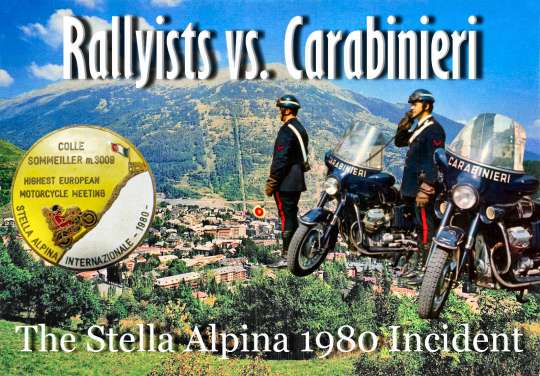

Stella Alpina Rally

1980

Sunday, 13 July 1980, should have been bathed in golden sunlight. As every year, Luigi’s restaurant — the unofficial headquarters of France’s most devoted motorcycle touring fanatics — was buzzing.

Tables overflowed with friends, laughter rang out, jokes flew, and cold beers clinked. Even the surrounding mountains seemed to approve, standing tall as silent witnesses to the camaraderie. Everything breathed friendship, brotherhood, and the thrill of the open road.

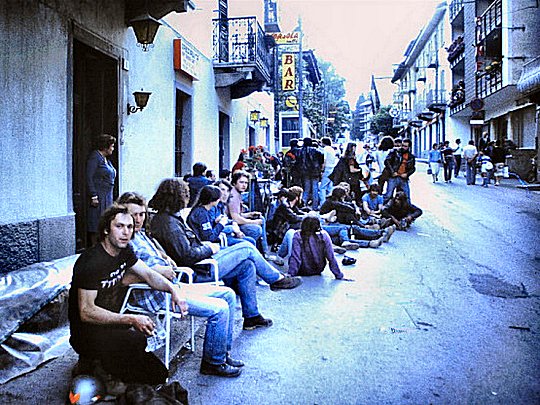

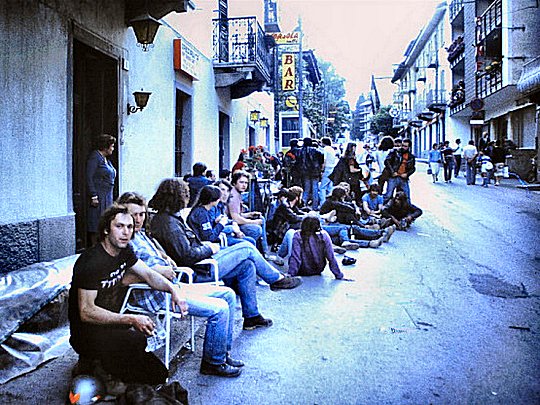

French or British, no matter — Stella Alpina is for cafés, laughs, and a cold drink in hand.

The Rally That Went Wrong

Then came the bus, inching down Via Medail, the main street squeezed tight like a bottleneck. On one side, our motorcycles stood neatly lined up in front of Luigi’s; on the other, a carabinieri vehicle sat planted across the road, a defiant barrier. It was clear it had been placed there deliberately, a monument to authority.

One small push and it could have moved, letting the bus pass with ease. But no — Italian police chose instead to command us, the riders, to clear our machines, as if bending to their will was our only option. Cooperation? Clearly, that wasn’t on the agenda.

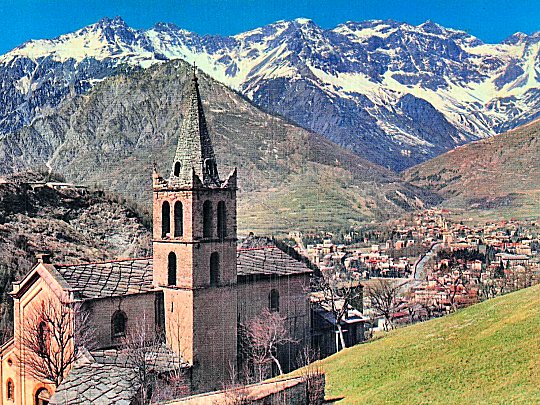

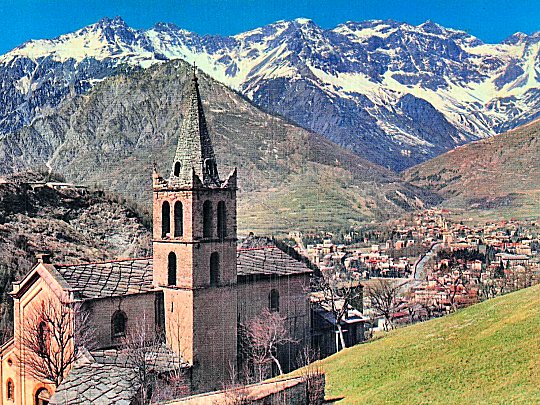

A pack of French riders gathered outside Chez Luigi, the summer HQ of Gallic rallyists (photo taken July 1981).

What happened next was beyond belief. It came suddenly. Brutally. Surreally.

As some riders began to shift their motorcycles, the leader of the unit — a brigadier named Antonio Cutillo — lost all sense of control. That name — I have never forgotten it. Forty-five years have passed, yet it lingers in my memory as if it were yesterday. You never forget a man capable of turning a calm, sunny afternoon into sheer chaos.

Everything flipped in an instant. Brigadier Antonio Cutillo struck without warning. No provocation, no hesitation — he lunged at them, pistol in hand, shielded by his armed men.

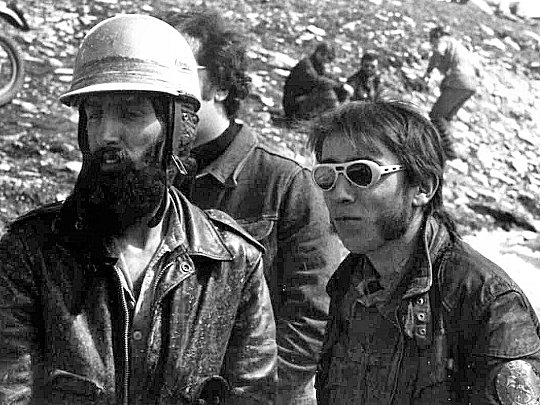

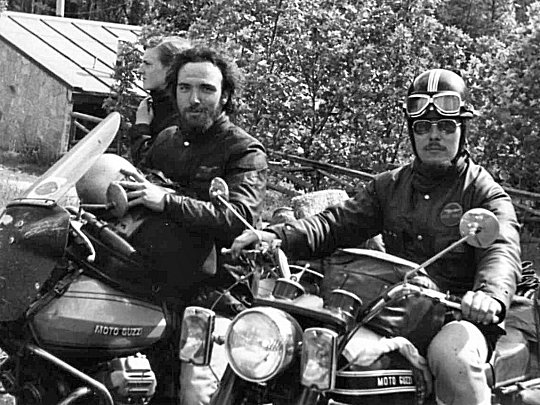

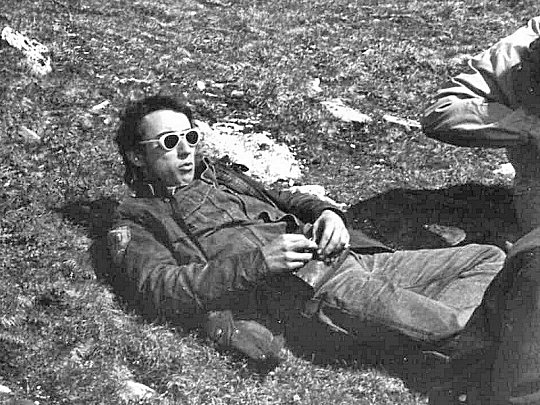

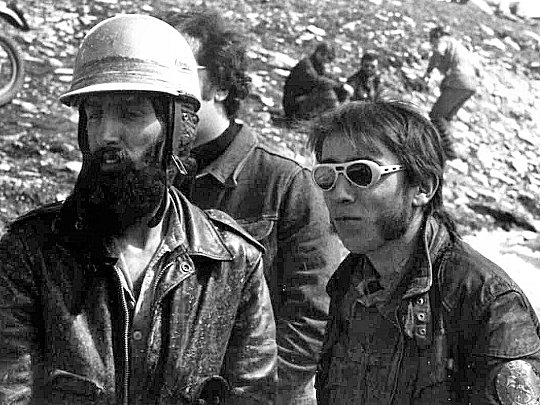

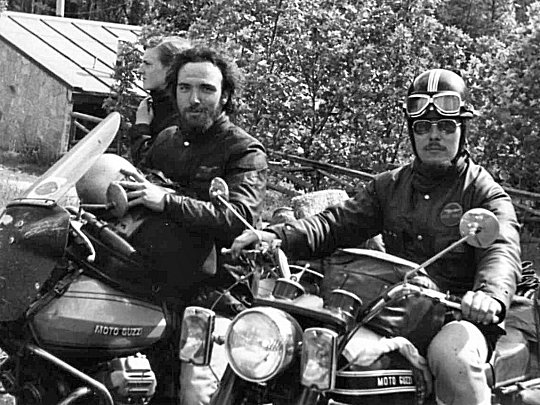

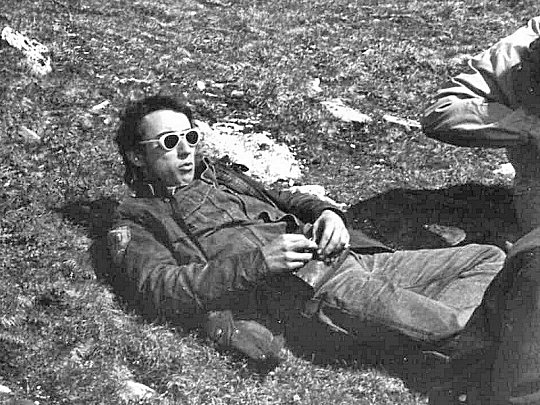

Yours truly (r.) here with Hervé Bully (l.). By sheer luck, when the brigadier lost it, I was out of his line of fire, watching the chaos — sky-blue shades, Elvis sideburns, and high as a kite. Dodging a beating that afternoon? Absolutely priceless.

The blows came down quickly. Those with long hair, a jacket, or simply a face the officer didn't like were pinned to the ground, handcuffed, and taken to the station like real criminals. The sound of the impacts and the cries of the victims echoed in the street, while witnesses could only stand by, helpless.

At the station, the situation did not improve. Fists and batons were used on six of them: Jean-Louis Beltram aka ‘Toulouse’, Jean-Marc Roquet aka Genese, the late Belgium Phil Van Vlemmeren, and three other friends.

When they were released, they bore the marks of the violence. Their injuries attested to an unprovoked and unjustifiable use of force.

While they endured the blows, a tow truck carried off several motorcycles, their owners away at a nearby fair, unaware of the chaos awaiting them.

Jean-Louis Beltram, photographed here on his trusty Moto Guzzi at the campsite, the day before the incident. Little did he know that the next day he would be arrested, taken to the station, and given an Italian-style beating.

Leadership Absent, Authority Misused

The sun continued to shine over Bardonecchia, but for us, the Stella Alpina had lost a bit of its light. What should have remained a friendly, festive gathering had been marked by injustice and violence.

Laughter had vanished from the celebration. And in the eyes of the gathered riders, a single thought was clear: disbelief, and the bitter certainty that the Stella Alpina would never be the same again.

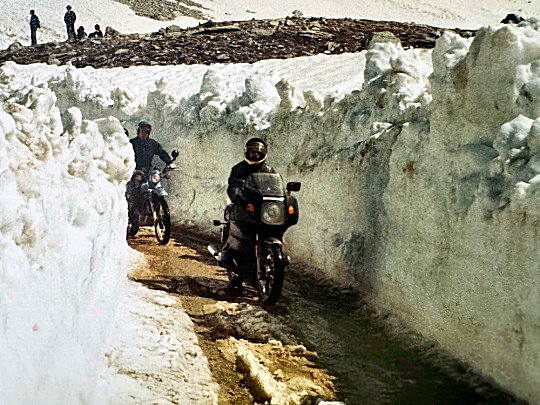

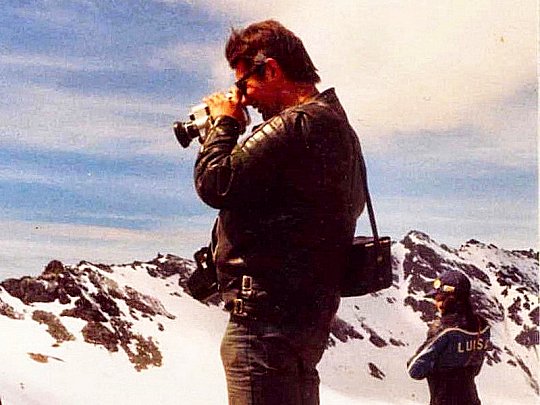

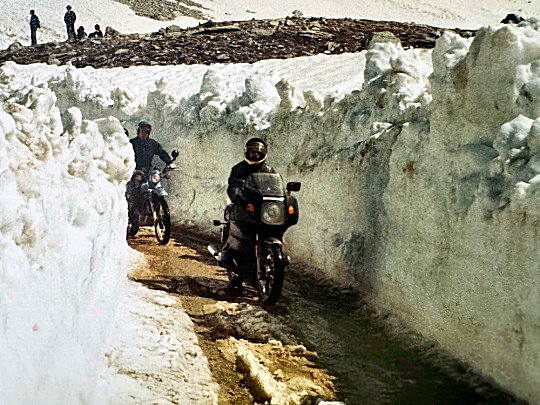

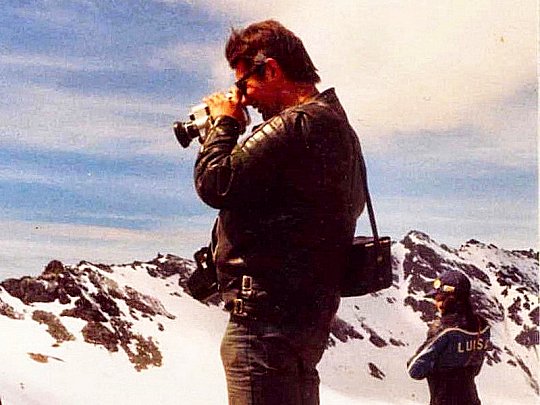

Sunday morning at the summit — rallyists basking in the sun and the glory after conquering the Colle del Sommeiller.

One of the main causes of these incidents was the absence of the head of the Carabinieri, who had been stationed in Bardonecchia for many years and was therefore fully familiar with the Stella Alpina and its gatherings. That weekend, he was on leave in Turin.

Taking advantage of his absence, his subordinate, Brigadier Antonio Cutillo, temporarily in command, seemed eager to make his mark in the boss’s place.

According to Bardonecchia’s shopkeepers, who were shocked by the violence that occurred that Sunday, Cutillo had a habit of abusing his authority — and this was far from his first excess.

The journey was tough, but the reward of this view makes it all worth it.

To make matters worse, the other Carabinieri present were young recruits, recently assigned to Bardonecchia from various regions of Italy. Unfamiliar with the traditions and customs of the Stella Alpina, they could do nothing but follow their superior’s orders blindly, contributing to an atmosphere of tension and clumsy enforcement that could easily have been avoided.

One might almost have wondered if a curse had fallen on the 1980 Stella Alpina. After the afternoon nightmare with the Carabinieri, everything seemed to spiral further into chaos.

When your friends say 'trust me, it's a shortcut

A Sunday without Celebration

For many years, Sunday evenings had been the unmissable gathering: the French community would come together to celebrate the end of the rally at the café-restaurant of our friend Luigi, alongside his sister Lucianna and her husband, Mario Viarengo, an exceptional cook.

But that year, things were off to a bad start. After the violence of Brigadier Cutillo, who now had the motorcycle community squarely in his sights, and after our Italian hosts had suffered the consequences of his abuses, the café was temporarily closed. The long-awaited celebration could no longer take place, and the mood of the participants suffered even more.

En route where the paved road ends and the off-road adventure begins

Despite everything, our hosts took the risk of defying the ban and continued to serve us drinks — not inside the establishment, but discreetly in their garden.

Later in the afternoon, I met up with a group of friends at a pizzeria. They quickly filled me in on the latest news — of course, none of it good. The first was that many French participants, disgusted and disheartened by the day’s incidents, had already crossed back over the border, cutting short what was supposed to be their vacation in Bardonecchia.

As jammed as Bangkok streets on a Saturday night

Among them were a group of young riders from Pornic, in Brittany. They had traveled nearly 960 kilometers on their Kreidler mopeds to experience, for the very first time, the Stella Alpina that had been so highly praised to them.

Imagine their disappointment. They turned back, deeply disheartened. One of them summed up the rally with these words: “The Stella Alpina, the highest rally in Europe… but also the most policed.”

Caught in Bureaucracy: The Campo Smith Fiasco

Since the very first time I took part in this rally, we had always pitched our tents at the same traditional campsite in the heart of town, known at the time as ‘Campo Smith.’

In July 1980, staying true to tradition, we set up our tents there once again. That year, a large British delegation camped alongside us, mostly familiar faces, including our longtime friends Rodney Taylor and Colin ‘Codge’ Harris.

Colin Harris aka ‘Codge’ – (left) in the late ’70s at the Bois-Renard Rally in Normandy; (right) at the 2013 Stella Alpina, alongside Heather MacGregor.

The atmosphere, usually so friendly, had turned to suspicion and tension. As a telling anecdote — one that illustrates just how on edge the Carabinieri were that year — Codge, a true gentleman incapable of any provocation, was punched square in the face by a policeman. His only “offense”: defending his partner after a Carabinieri had roughly shoved her.

Sidecar on air, bike on ice — Alpine parking, unlocked.

But the second piece of bad news was far worse: my friends revealed that the Carabinieri had issued an ultimatum — every camper had to vacate the site by 9.00pm. We had only a few hours to gather our gear, dismantle our tents, and find somewhere else to stay.

The reason? According to the police, we were “illegally” occupying Campo Smith. The absurdity was staggering: some campers had been there for several days, yet not a single local official — or even the police themselves — had come by to inform anyone that their stay was forbidden.

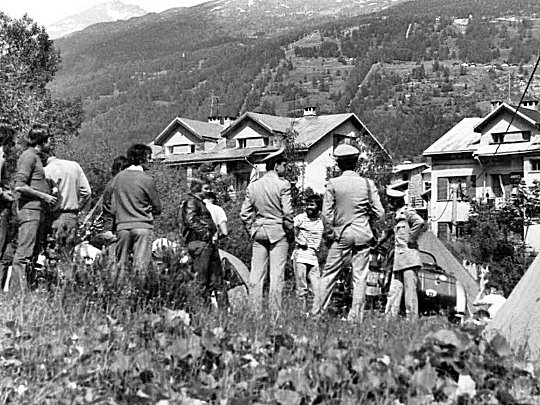

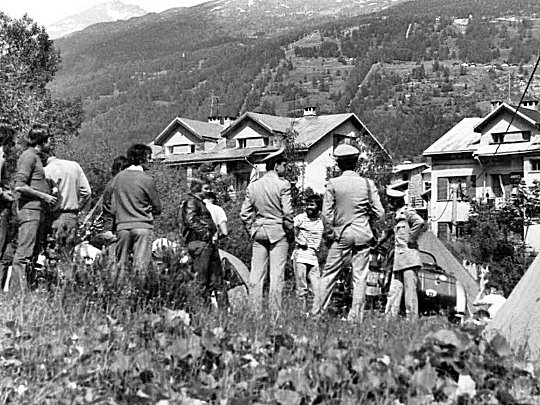

The Italian police at Campo Smith. We were in their sights. Their ultimatum was clear: pack up and be gone before 9 p.m.

We later learned, through Italian contacts, that three months earlier the mayor, Mr. Gibello, had summoned the late Mario Artusio, the organizer of the rally, to inform him that, exceptionally, ‘Campo Smith’ could not be used that year.

Mario had been unable to attend the meeting at the time for personal reasons, which had already upset the local authorities.

The Beaulard campsite, 6km from the city center, on the road to Turin, had been planned as an alternative site. The problem: no participant had been informed.

Even worse, there were practically no signs or markers along the route to indicate the way to the Beaulard campsite. Most of the riders ended up camping more or less anywhere, completely unaware that they had unknowingly placed themselves on forbidden ground.

Claude Major (left), early ’70s secretary of MC Dragons’ Popoufre Section, and the late Michel ‘Pirana’ Lecoq (right), taken far too soon by illness.

No Hard Feelings, Only Memories

I was not the only one who thought that Mario Artusio might have borne a small share of responsibility for this organizational lapse.

Sadly, not a single rallyist had been informed — neither by Mario himself nor by representatives of the town council — about the issue with Campo Smith until late Sunday afternoon.

Among the French rallyists, some quietly suggested that Mario, with all his enthusiasm and passion, had perhaps devoted a little more of his time and energy to organizing his three-day Safari — his pride and joy, which gathered a few dozen close friends — than to the rally itself, which each year brought together more than five hundred riders from across Europe.

Built entirely from scratch by a Breton rallyist: a quirky Moto Guzzi chassis paired with a 2CV Citroën engine, spotted at the campsite. A truly quirky bitza.

In an article I wrote upon my return, published in La Revue des Gueux d’Route, then the voice of the crème de la crème of French rallyists, I briefly mentioned this unfortunate misunderstanding. I won’t dwell on it again here. Time has softened old frustrations, and I prefer to remain silent, not wishing to cast even a bit of shadow over Mario’s legacy.

The call that ended the chaos

Exasperated by the situation and by the police violence, Mario Viarengo — Lucianna’s husband and the cook at Chez Luigi — decided that enough was enough. Using his connections, he managed to reach the chief of police in Turin by telephone to describe the unbearable situation in Bardonecchia.

Hugues ‘Gueguette’ Spriet, took most of the black-and-white photos here, keeping our motorcycle memories alive.

It is said that Brigadier Cutillo was severely reprimanded by his superiors. It must be true, because by Monday morning, not a single policeman could be seen in the streets. Calm had returned, as if nothing had ever happened.

Unfortunately, many friends had already left the town, taking with them the bitter memory of a weekend that should have been nothing but celebration and camaraderie.

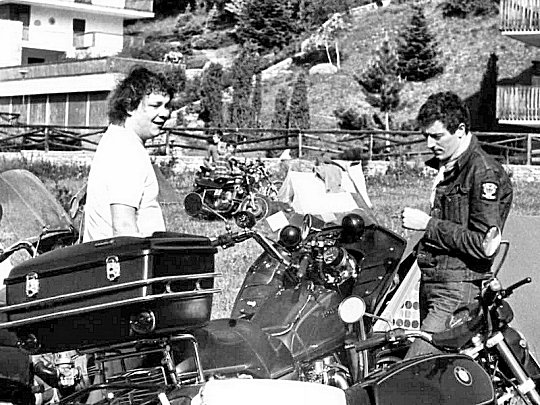

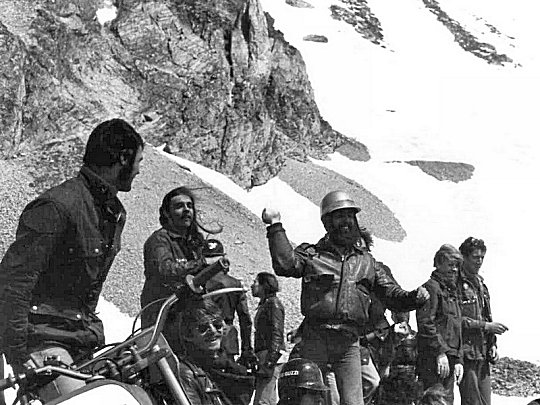

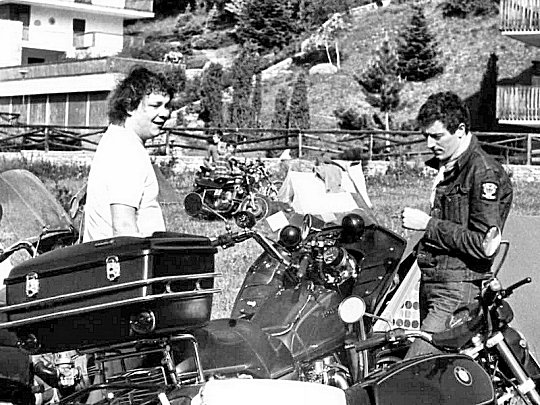

The ‘Gueux d’Route’ taking it easy. Herve Bully, one of the three founders, is here with Bachmann to his right, alongside the British classic bike enthusiasts from Chartres, led by Jeff Laroche.

As for the rally itself, I have vivid memories of the 1980 edition. I particularly remember an English rider who, on Sunday morning, tackled the Sommeiller climb and completed the two days of the Safari on a venerable Vincent 1000. There were also two magnificent single-cylinder Ariels, relics of another era and admired by all.

Year after year, the number of Italian participants, riding off-road motorcycles and arriving solely on Sunday morning, continued to grow. Most came as casual tourists, simply to ride up to the pass and buy the commemorative medal. That year, it cost 3,000 lire, with a sandwich and a drink included.

Yours truly, Sunday morning at the summit of Sommeiller, completely in ‘take-it-easy’ mode. By the afternoon, with the chaos at Chez Luigi, moods would shift fast.

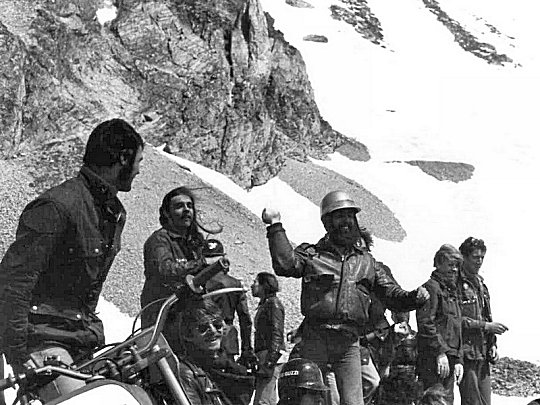

By the registration caravan, what had started as casual fun quickly erupted into a full-blown snowball fight. In the middle of July, resisting the temptation was impossible!

Snowballs flew in every direction, and naturally, Hervé “Le Grec” Bully and I were right in the thick of it, joined by a few other ‘Gueux d’Route’.

It was pure, unrestrained joy — a scene straight out of a carefree childhood, bursting with laughter and good spirits.

Summer snowball fight. The “Gueux d’Route” crew letting loose — featuring two notorious rascals: Sylvain ‘La Nouille’ Konig (long hair) and Hervé ‘Le Grec’ Bully (helmet on)

After the rain comes the sunshine: the mayor finally confirmed to Mario that there would indeed be a 1981 edition of the Stella Alpina. Good news that finally restored a bit of hope after so much tension and disappointment.

C’t’est là qui m’tapa

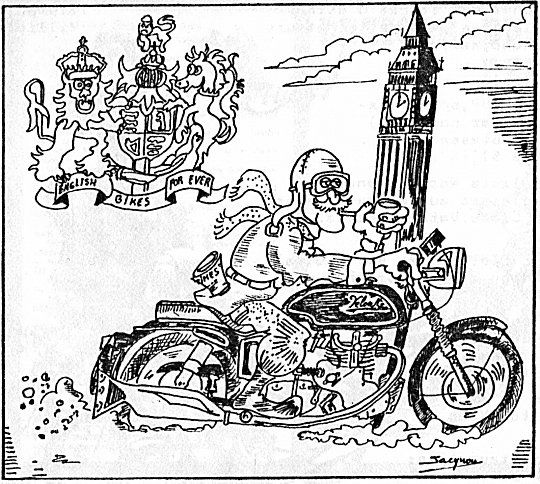

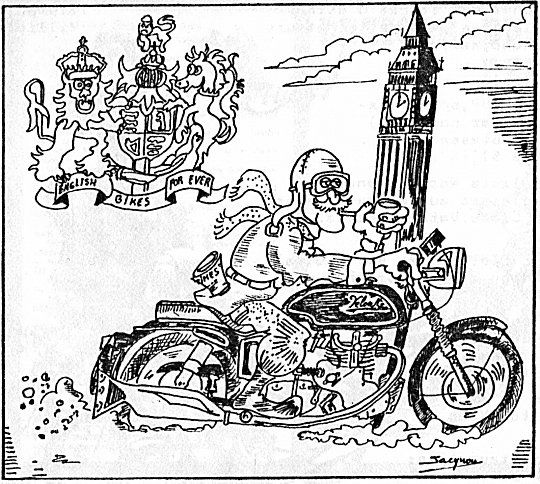

Some time later, I received at the editorial office of La Revue des Gueux d’Route, as I did every month — and for two and a half years while I served as editor-in-chief — a batch of new humorous drawings created by Jacques ‘Jacquou’ Lejeune, intended to illustrate the content of the upcoming issues.

The name may mean nothing to you, but Jacquou was, at the time, the talented official illustrator of this handmade magazine devoted to motorcycle touring and the rallying world. A gifted storyteller and a caricaturist of genius, overflowing with humor, he brought to life on paper delightful scenes from the rallies of the day and their wonderfully colorful characters.

It was only much later that I truly realized his real talent, and how much of a cornerstone he had been within our magazine’s editorial team. He deserves to be thanked and remembered for it — fully and rightfully so.

One of many drawings by Jacques ‘Jacquou’ Lejeune — just one among the hundreds he created week after week over two and a half years for La Revue des Gueux d’Route.

Among all the drawings, one in particular perfectly captured one of the brutal episodes of the 1980 Stella Alpina. The two characters depicted could have stepped straight out of a Guignol puppet theater — it was brilliant.

The moment I saw it, I knew it had to become a special commemorative Stella Alpina sticker. My plan was to distribute it freely to all the “martyr rallyists” who had been there — and endured stress, moral injury, and the lingering shock of that day.

And so it was done. After finalizing the logo, I added a title for the sticker based on a subtle play on words: “Stella Alpina Rally” became “C’t’est là qui m’tapa” (meaning “That’s where he hit me”).

(left): Jacquou and yours truly at the 2013 Gueux d’Route Rally in Sarlat, Dordogne; (right): the Gueux d’Route pirate creation in all its glory.

When the magic faded

Since the early 1970s, I had never missed a Stella Alpina gathering. Year after year, I had been a loyal regular, drawn by the camaraderie, the mountains, and the thrill of the rally.

But after the events of 1980, a bitter taste lingered. I forced myself to return in 1981, yet the excitement and passion I once felt were gone. The rally no longer held the same magic for me — and I never went back again, leaving behind a chapter that belonged to another time.

Gallery

Click on a small photo to enlarge it. Then scroll to the bottom of the photo set and click the "Add Caption" button. Type in what you know about the time, place, people, bikes. Or just something random. When you have written something, the Contact Centre will slide out so you can check your message before sending it. Please add your name and email address and click "Send"

A second testimony regarding that lamentable meeting in July 1980 confirms the accuracy of my report. Below is a verbatim copy of the letter sent via diplomatic pouch on 16 July 1980 to the Ambassador of Italy in France, under cover of the Italian Consul in Grenoble. The letter was written upon his return from the Stella Alpina by the well-known Ardèche rally rider Pascal Bouculat, aka ‘Bocu’, a close friend of Jean-Marie Debonneville.

- Jean-Francois Helias

Mr Ambassador,

I have the honour to draw your attention to the following events.

Last weekend, together with members of my motorcycle club, I travelled to Bardonecchia (Province of Turin) to attend a motorcycle rally held at the summit of the Sommeiller Pass. During our stay, however, we had serious cause to complain about the conduct of the Carabinieri, whose actions appeared to us to be wholly unlawful.

Allow me to summarise the facts.

On Saturday evening, a group of French riders, joined by several British and Belgian participants, gathered at Luigi’s Bar on Bardonecchia’s main street. After the bar closed, we remained outside, quietly explaining to those unfamiliar with the Sommeiller site how to reach the summit via the so-called “difficult road”, a 25-kilometre ascent to an altitude of 3,009 metres. This took place at around one o’clock in the morning and, I wish to emphasise, without any disturbance or noise. Nevertheless, the police abruptly ordered us to return to our accommodation, doing so in a rather heavy-handed manner and with machine guns visibly at the ready.

The following afternoon, while descending from the pass, we returned to Luigi’s Bar to have a drink. As on the previous day and in previous years, our motorcycles were parked in front of the establishment. Luigi, the bar owner, is well known to regular French participants in the Stella Alpina rally and has long maintained friendly relations with us, even sharing in the mourning of a motorcycle club from Clermont-Ferrand after the death of its president three years ago.

At around 6 p.m., the situation suddenly deteriorated. The police carried out a raid in the street and inside the bar, conducted identity checks, and ordered us to remove the motorcycles parked outside. This proved difficult, as several owners were not present, having gone for a walk through town or to the funfair. It should be noted that, barely an hour earlier, there had been neither signage nor any indication from the police that parking in this location would suddenly be prohibited.

A tow truck subsequently removed several motorcycles, and six individuals were taken to the police station by the Carabinieri without any apparent valid reason. They were roughly handled before eventually being released.

Upon returning to the campsite to change clothes before going out to eat, we discovered Carabinieri officers opening and searching tents and motorcycle saddlebags. An officer then informed us that all French nationals, without exception, were required to pack up and leave the town before 9 a.m. the following morning.

This ultimatum, delivered without any apparent legal justification and directed at citizens of a foreign — and supposedly friendly — country, under the threat of machine guns wielded by what could only be described as “young men in uniform”, compelled me to bring these facts to your attention. We complied with the order, packed our tents, and attempted to contact the French Consulate in Turin. Predictably, at 8 p.m., we reached only an answering machine.

The sole purpose of this letter is to set out the facts of which I, along with other French citizens, was a victim during this weekend. For more than ten years, I have taken part in motorcycle rallies throughout Europe, both on this side of and beyond the Iron Curtain, and never before have I experienced such harassment over such trivial matters.

Is it, then, the mere fact of wearing a helmet that alters one’s status under international law? If so, judging by the number of machine guns aimed at us, I can only assume that I was mistaken this weekend for a member of the “Red Brigades.” Such treatment does nothing to foster goodwill between peoples, and several members of my club, for whom this was a first visit to Italy, are now unlikely to return.

Mr Ambassador, please accept the assurance of my highest consideration.

Pascal BOUCULAT

Roiffieux, 16 July 1980

Thank you very much for all these detailed explanations about that tragic Stella 1980 meeting. It is something we have never forgotten, and like many other rally enthusiasts who were present at the time, it has remained painfully stuck in our throats ever since.

Thank you very much for all these detailed explanations about that tragic Stella 1980 meeting. It is something we have never forgotten, and like many other rally enthusiasts who were present at the time, it has remained painfully stuck in our throats ever since.

I had the opportunity to return there later on, in 2013, 2014, and again in 2017, together with our common friend Gilles Gaudechoux. While it was meaningful to be back, those reunions no longer have much in common with the ones we experienced in the 1970s.

Despite everything, we are left with many wonderful memories from those days.

- Jeff Laroche

It’s an incredible story that I had missed while covering rallies for Motor Cycle Weekly.

It’s an incredible story that I had missed while covering rallies for Motor Cycle Weekly.

- Dave Richmond

The Contact Centre also includes an option to send your response by email. Choose that option and you can attach scans of your own photos for us to add to the page.

Thank you very much for all these detailed explanations about that tragic Stella 1980 meeting. It is something we have never forgotten, and like many other rally enthusiasts who were present at the time, it has remained painfully stuck in our throats ever since.

Thank you very much for all these detailed explanations about that tragic Stella 1980 meeting. It is something we have never forgotten, and like many other rally enthusiasts who were present at the time, it has remained painfully stuck in our throats ever since.