Dragon Conception

Dragon Rally conception by John Ebbrell, tracked down by John Nutting, Dave Richmond and Jean-Francois Helias.

The spark that lit the Dragon Rally's eternal fire was struck by Harry Louis, editor of The Motor Cycle.

Harry Louis, doing what he loved. How much we owe to this man.

It was fanned into flame by John Ebbrell. The story was recounted in The Motor Cycle on 28 December 1961 and is reproduced here, thanks to the efforts of the above researchers.

THE MOTOR CYCLE, 18 DECEMBER 1961 pages 810-812 WALES IT MUST BE John Ebbrell Searches for an Elephant

In Snowdonia - and Finds a Dragon

AS I drank my coffee, I watched the sunset fade behind the distant mountains. "I've got a special job for you," Harry Louis had told me. "Motor cyclists all over the country are demanding a British Elephant Rally — and they want it soon. Go to North Wales on a recce for a place to hold it." Here, without doubt, was the ideal area. Wales is a respectable run from Birmingham and the industrial North, yet within a weekend's reach of hard riders Less than five hours out from London I was already in the hills. And before I was to leave, I had found the ideal spot. Bryn Bras Castle, night at the foot of Snowdon. Remember the name: Bryn Bras. Here was no empty shell, but an hotel and restaurant as well as a castle. Conway Club chairman Don Williams and I discovered large, well-furnished rooms With fireplaces in the baronial style, set in a maze of passages and stairs. It would be just the thing for the friendly get-togethers motor cyclists love; plenty of room for hundreds of riders, yet cosy enough for the smallest party. There was light, warmth, somewhere for a wash and to leave riding kit. A barbecue or buffet supper could be arranged for any number. No Shortage of parking space in the grounds either. A few of the crowd — perhaps 80 - could stay overnight in the castle proper. Camping facilities were available, too. The management would welcome the rally at Bryn Bras. We could rent the whole place, make it our own for one night. But back to the story that led to the discovery. All the way up that splendid hard-in-third-gear climb out of Llangollen, the Leader's headlamp turned each cat's-eye into a tiny lighthouse. A5 is the gateway to North Wales. In whichever place the rally was held, the bulk of the riders would travel this road, climbing the moors after Corwen, winding up the grip along the two-mile straight from Cerrigydrudion. The luck of a clear day would give them a tantalizing glimpse of Snowdon itself before they dived down the tree-lined bends into Betws-y-Coed. "Is there a Leverkus in Caernarvonshire?" Indeed there is - nearly 50 of them — for the Conway Club invited me to discuss the rally with them. Their clubroom, in the shadow of the famous castle, was crowded that night, for though the club is modest in membership figures, there is no lack of enthusiasm. Like thousands of other motor cyclists, their imaginations had been fired by George Wilson's call for an Elephant Rally in Britain. There were riders here tonight from all over North-west Wales; they knew the district; they had the contacts, When did they want the rally? February. How soon did they want to start? Now! We quickly got to work. However tough rally riders might be, they would demand certain facilities - a roof over their heads, a hot meal, a warm fire, a place to clean themselves up, somewhere to spend the night. The last problem was easily solved. Everywhere in North Wales there are hotels, inexpensive guest-house and farms, and camping sites for the hard men. It would simply be a matter for the organizers to collect addresses within a ten-mile radius of the meeting place.

Photo 1 caption: Will this be the Mecca for hundreds of enthusiasts? Bryn Bras Castle, at the foot of Llanberis Pass. That was going to be the ticklish point. Wales has nothing to equal the Nürburgring in Germany, with its assembly hall, restaurant and all the rest. Somebody suggested an hotel. But where could one big enough be found? The Nürburgring attracts 1,000 riders. Besides, who was going to ride 300 miles just to go to an hotel? Something more dramatic, more in the spirit Of the thing, was demanded. A castle would be the very place! Wales was full Of them. So we must find one with at least the minimum mod con. Their home-town castle was therefore out of the picture, but the Conway boys told me that 15 miles along the coast, close to Bangor, stood Penrhyn Castle. It had been built by a 19th-century millionaire; now it was in the hands of the National Trust. So, two days later, Don Williams and I took the magnificent corniche road to Bangor. Penrhyn Castle was palatial beyond description. We went in to meet the National Trust authorities. But it was no go. An "Elephant" would be too unconventional for them. "Next year, perhaps," was the nearest we got. "Why not Glynllifon, south of Caernarvon?" suggested the information office in Bangor. This, turned out to be a mansion owned by the County Education Authority, for residential courses. Set in parkland, it looked attractive enough through binoculars, but a check with the County Offices closed the matter. There was no accommodation for large parties. "Nitor," had thought an airfield would make a grand setting. So I had a look round the old R.A.F. station at Llandwrog. Set on a sand-spit at the bottom of the Menai Strait and swept by a howling gale, it seemed like the end of the earth. The runways stretched gaunt and deserted; the buildings were mere shells carpeted with cow dung. Nothing here for us. It was the same story at Penrhos airfield, below Pwllheli. Well into the Lleyn now, that peninsula which stretches into the Irish Sea, I carried on through Abersoch to Hell's Mouth. During the war an airfield had been built on what the Welsh call a morfa, or salt marsh, but today only crumbling air-raid shelters remain. My guide referred to a mansion at the other end of the bay, called Plas-yn-Rhiw. Plas in Welsh can mean a palace, but this was only a quaint little country house perched high on the tree-clad hillside. Three elderly sisters live there now. They made me a cup of tea and showed me a turret staircase in the oldest part of the house built, they said, by Prince Meirion Goch who came to win back his lands from the Vikings, 1,000 years ago. Far below, the white surf crawled in the aptly-named Hell's Mouth. What a pity the place was small! Photo 2 caption: This wonderful panorama of Snowdon will greet riders as they make their way from Capel Curig

Map caption: This map is based on the Ordnance Survey: Crown copyright reserved Back in Conway, the club's committee and I started a process of elimination. Anglesey was out altogether. Stately homes were non-existent and the service airfields were all in some sort of use. A call to Butlins at London scrubbed the possibility of their Pwllheli holiday camp - unless someone presented us with the £3,000 needed to open it! The Ministry of Works Cardiff head-quarters seemed sympathetic when we approached them, but the castles in their charge - Beaumaris, Caernarvon, Criccieth — were as devoid of facilities as Conway. Harlech, the most promising of the bunch, would be closed for off-season repairs. Next morning I set off to do the rounds of the climbers' inns in Snowdonia. (They should be used to large parties of young, jolly men.) That day the rain came down in torrents and it blew a howling gale. The welcomes I received were, I am sorry to say, scarcely more encouraging. "People come here for peace and quiet," the proprietress of one place told me. "Writers and artists stay with us in the winter. They couldn't do with the noise of all your motor bikes." I started up the Leader and squelched off down to Caernarvon. I had heard of a public hall there, called the Pavilion. The Pavilion turned out to be nothing but a tumbledown tin shack. Nursing a cup of tea in a nearby café, I browsed through the town guide. Bryn Bras Castle, the advertisement read, offers you a welcome... I discovered Bryn Bras, five miles east of Caernarvon, just off the Llanberis Pass road. The turrets and battlements glimpsed above the tree tops gave it the mystery and romance of a castle of fairyland. Could this, at last, be the place? Yes, I say. When I set off back to London I went round by Bryn Bras, and at the top of the hill behind the castle anchored up. In my mind's eye I saw the towers floodlit, the place thronged with riders from all corners of the kingdom, the same nocturnal cavalcade down the Llanberis Pass that reader D. R. Shackles had envisaged a fortnight ago. On this same hill the celebration bonfire would be seen, winking and glowing below the snow-capped mountains, a signal that these men had come to this distant spot to pay homage to the greatest game in the world. I thought, too, of the enthusiasm of the Conway Club, their willingness to play host to this memorable event. They were eager to be at work, translating vision into reality; to go into the details to see whether a February dare could be arranged. Already they had their own name for it, the proud symbol of a proud people — the Dragon Rally. North Wales it must be! Photo 3 caption: The same mountains in a different mood. Through lashing rain, John Ebbrell fights his way from Pen-y-Gwryd up to the Llanberis Pass

John Nutting, who finally traced the above document, recollects his own experience of the Dragon Rally (and others)

Dragon rally memories

I didn't know of Harry Louis, editor at The Motor Cycle and his formative influence on the Dragon Rally's history in the early 1960s. I would find out much later when I worked for him as a trainee journalist at the magazine from 1972.

When I say memories, they're more recollections of going to the Dragon Rally three times, the first I think in 1967. At the time I was studying Mech Eng at Newcastle, and was riding a Lambretta TV175 scooter, but for some reason it was off the road. So I rode pillion with my posh mate Derek Parker who owned a very smart BMW R69S, which was probably the most expensive machine you could buy then.

It had been snowing over the peak and I can recall being perched on the back of the Bee-Em as we tip-toed on packed ice going south on the M6. Progress was slow, so we only made it to Warrington before dark. Cold and miserable, we decided to find digs and in a pub we were directed to this adjacent house where a kind lady took pity on us, provided ham sandwiches and showed us a dormitory where coughing bodies were already in bed. It was the longest night ever.

But we made it to Llanberis, and probably camped, and made it back to Newcastle.

By the next year, I'd seen the light after taking a holiday with relatives in the Isle of Man, being overwhelmed by the sight of the Southern 100 races (especially seeing Sid Mizen racing his Manx Norton) and replaced the Lambretta with a Norton 99 Dominator, a lovely red machine which I think I'd soon after converted to 12v electrics. It had coil ignition and I can recall later riding to Newcastle and passing the motorcycle shops in the west end when it stopped as I turned into the Elswick Road. Funny how details like this stick. Investigating the ignition cover I found the rotor had sheered off. A short walk back to the shops and I bought a replacement, so I was on my way to my shared house in Dipton Avenue.

It must have been that year, likely 1968, when we battled through February rains to get to North Wales and the Dragon, not having learnt any lessons. I knew North Wales well, having toured two-up with a mate on my LD125 Lambretta in 1964 to view the remaining narrow-gauge railways, including the quarries at Dinorwic and Llanberis. You'd think it'd be easier on the Norton, but having to ford a flooded river at Kirby Stephen beforehand to get there was just the start.

We made it to Llanberis, but the dry ground was packed with bikes so we had to resort to using the quarry buildings which were under half a foot of water but had the benefit of wooden pallets that we used to get above the water line with our sleeping bags.

I can't remember the reason but rather than return to Newcastle, we rode back south to London. Somewhere north west of Birmingham, the Norton stopped again with what turned out to be a broken primary chain, no doubt a legacy of being doused in water in the earlier flood (of course the primary chaincase isn't completely water proof).

Luckily I had spare links for the chain, so we could get going again, but without an alternator, because the flailing chain had wrecked the windings. So as evening approached and the twin 6v batteries weakened and the lights dimmed we rode in convoy, but we made it back home, just.

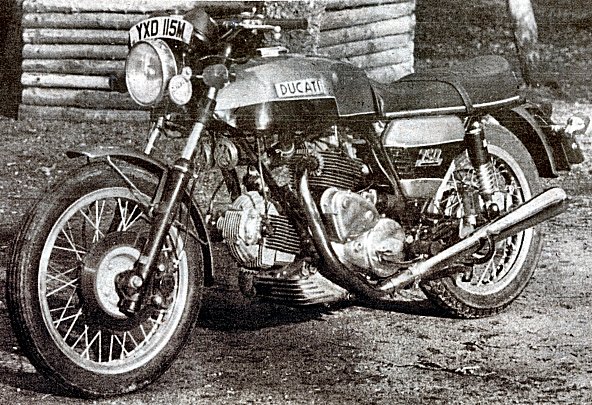

I probably vowed never again to brave the miserable journey, but after working at the paper for a couple of years in the company of John Ebbrell who was always hatching crazy new projects I found myself persuaded in 1974 to take a Ducati 750GT to the Dragon. I can't remember if Ebbrell accompanied me but the ride up along Telford's A5 was a breeze, the big vee-twin loping through the curves and beyond Betws-y-Coed to the rally site which this time had been carefully selected in what was a swamp on the side of a hill.

Entering the field I managed to fish-tail the bike to some reasonably less muddy ground to be welcomed by bike fans raving about the Ducati, which was a rare beast in the UK at the time. One lesson that had left its mark was to avoid camping in misery, even though the company may be fun, and I had organised a B&B where I escaped to find some comfort. I think that's what I did.

At Motor Cycle we had ‘staff bikes', the first I had experience of was a Norton Commando Fastback that was used mostly by Harry Louis as I recall. After testing a BMW R75/5 flat twin in1973 we asked to keep it for a while, and that bike proved to be reliable workhorse. While testing a Yamaha DT175 trail bike it was suggested, probably by Ebbrell again, to ride it to the Elephant Rally in the Eiffel Mountains. Dutifully I set off down the A127 to Southend to catch the ferry flight to Dunkirk. But half way there, the two-stroke seized up and I had to limp back and grab the Bee-Em. That was an amazing trip: there wasn't time to pack a tent so I dossed at a lovely hotel near the rally venue.

I don't know if the National Rally counts as a rally as such, but in 1974 it was Ebbrell again who hatched a scheme to cover as many miles as possible over the week on the most unlikely machines. The challenge was in 24 hours over a weekend to cover 600 miles and checking in to as many clubs as possible to get the maximum points and thereby qualify for the final average speed test for a gold award. Ebbrell, being a dyed-in-the-wool Rawstenstall masochist, selected a French Velosolex moped barely capable of 30mph, while I was provided with a 1914 Model P Triumph, all sit up and beg with pedal assisted starting supplied from the museum at Rex Judd's in Edgware.

We reached Trentham Gardens in Stoke on Trent but if I say that I covered only 110 miles which sounds a bit weedy, let me add that it was one of the most tough and scary rides of my life, made worse by a broken pedal chain that made junctions particularly hairy when dodging between the cars, and having to remember how to juggle the throttle and advance levers to keep the machine chugging up hills as traffic built up behind me. I don't remember (there I go again) getting any credit for that apart from an ACU or the like document.

Harry Louis had retirement in mind by then and soon after set off to run the Speedway Control Board. The Motor Cycle staff also moved from 161-166 Fleet Street to IPC's new home at Sutton in Surrey where the title was to be led by Peter Kelly, who came south to have more fun. He of course had previous, having worked for Motor Cycling back in the early 1960s. Which sort of brings us full circle.

- John Nutting